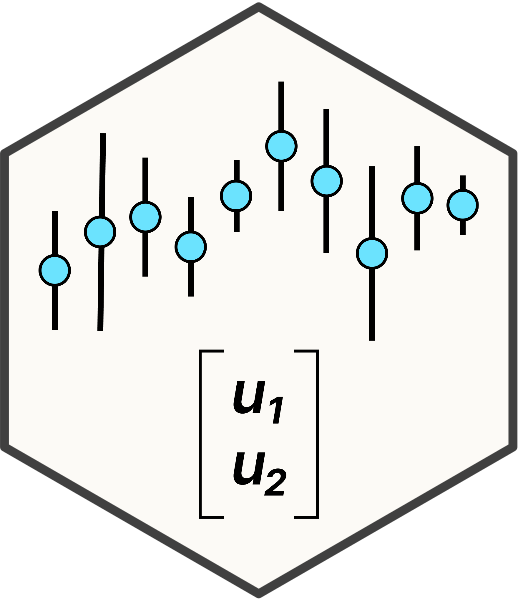

graph TD A[Define Research Question] --> B[Evaluate Data Quality] B --> C[Fit Model] C --> D[Check Model Assumptions] D -- Met --> E[Conduct Inference] D -- Unmet --> F[Check data or consider others models]

4 Model Preparation and Flow

This chapter provides a brief introduction to the steps involved in data analysis using linear mixed models and some thoughts on data quality and data interpretation.

The steps explained below were applied to all example analyses.

Analyzing data using linear mixed models involves several key steps, from data preparation to model interpretation. Here’s a structured approach:

4.1 Step 1: Define the Research Question(s)

It is important to define what is your question that you want to answer with your research data because it directly influences the model specification, interpretation, and validity. This was determined prior to design of the experiment and data acquisition. However, things change as an experiment unfolds, and sometimes experimental aims become lost in translation between the original grant proposal for a prioject and when a graduate student eventually implements the experiment. Before embarking on an analysis, write down the goals of analysis in the most precise terms possible. Examples:

We want to know how much barley yield change as the result of this new fertilizer source compared to another source.

We want to estimate the change in milk yield with each unit change in cow parity.

We want to know if the drug has a stronger effect on reducing cholesterol rates where a difference of 5 units or more is considered a meaningful result.

We want to know the relative contributions of location, year and cultivar influencing barley yield across southern Idaho.

The first two examples are asking for specific inference on the estimated effects of a particular intervention. The third example is a hypothesis test, and the fourth example is also inferential, but focused on variance instead of point estimates.

For example, We conducted a randomized field trial to study wheat yield response to different nitrogen fertilizer treatments. In this case, we want to analyze how wheat yield responded to the fertilizer treatments. The next step is to identify the dependent variable (yield), and the fixed effects (treatment) and random effects (replications) in the experiment design.

4.2 Step 2: Conduct data integrity checks

The first thing is to make sure the data is what we expect. Here are the steps to verify our data:

4.2.1 1. Check structure of the data

In this step, we need to make sure that class of variables in data is as expected e.g. replication or block and Year are often in the numeric format after import into R. But, for analysis the replication unit and other variables that are not truly numerical1 needs to be in a ‘character’ or ‘factor’ format. The dependent variable must also be in the correct format for its intended data type. For this tutorial, the dependent variable is expected to be numeric in all cases2, although categorical outcomes are certainly plausible.

1 no one views 2025 as 2,205.

2 Since this tutorial is exclusively focused on general linear models and is not addressing generalized scenarios at all.

Most R import functions (e.g. read.csv(), read_csv(), read_excel()) interprets continuously varying numbers (correctly) as numerical variables, but if they do not, that is often a signal that there is an unexpected character in a particular column of data that is incorrectly read as non-numerical. Perhaps a comma is present when a period is expected, or “N/A” instead of “NA”. This is an indicator to double check your data to ensure there are no errors in it.

We can use the base code str() in R to look at the class of each variable in the data set.

str(dataset)This code outputs the data class of each variable present in the dataset.

The example code below shows the conversion of rep from numeric to factor class and the conversion of yield from character to numeric class.

dataset$block <- as.factor(dataset$block)

dataset$yield <- as.numeric(dataset$yield)Often, factor and character object classes are used interchangeably. However, we need to keep in mind the differences between these two classes. A character variable represents data stored in a text or “string” format. A factor variable is a categorical variable type with values stored as set levels. Most linear modeling packages in R expect categorical independent variables to be formatted as factors, however, many will also automatically convert character variables to factors.

4.2.2 2. Inspect the independent variables

Running a cross-tabulation across treatments and replications is generally enough sufficient to make sure ensure the expected levels of these factors are present in the data.

table(dataset$trt, dataset$block)The output from this code will give us the number of observations in each replication for a given treatment. It’s helpful to check (1) all the expected levels of categorical data are present and no additional levels are present (e.g., “high” and “High”); (2) the counts are as expected; and (3) what the balance of treatments is. Are they perfectly balanced? Slightly unbalanced? Very unbalanced? Is one treatment combination missing altogether? Depending on the context, these are resolvable issues.The main primary goal is to verify what the data looks like after import compared to your personal understanding of the data.

4.2.3 3. Check the extent of missing data

colSums(is.na(dataset))This will give you a number of missing values in each variable. Missing data is a normal part of experiments and in most cases not a problem. However, if there is more missingness than expected, it is good to check that the data are correctly entered and that nothing went wrong during data import.

We occasionally see users substitute missing data with zeros. This is not recommended at all unless there is a clear reason. If I planted an experiment and one plot failed to yield at all due to a field conditions, it is reasonable to assign a zero to that plot and variable. However, if I failed to plant anything in a plot due to user error, assigning a zero is not an accurate description of what occurred. Likewise, it not appropriate to treat true zeros as missing.

4.2.4 4. Inspect the dependent variable and all over continuous variables

Check the dependent variable and all continuous variables (i.e. covariates) to ensure their distributions are following expectations. A histogram is often quite sufficient to accomplish this. This is designed to be a quick check, so there is no need to spend time prettifying the plot.

The goal of this step is to verify the distribution of the variable and to make sure there are no anomalies in the data such as zero-inflation, right or left skewness, or any extreme observations (high or low).

hist(data$yield)Data are not expected to be normally distributed at this point, so don’t bother running any normality tests like the Shapiro-Wilk test. This histogram is a check to ensure that the data are entered correctly and appear valid. It requires a mixture of domain knowledge and statistical training to know this, but over time, if you look at these plots regularly, you will gain a feel for what your data should look like at this stage.

4.2.5 Next Steps

The purpose of these checks is to help us find any data errors that ought to be fixed prior to model fitting. They are designed to be done quickly and should be conducted for every analysis if you have not previously inspected your data as thus. We do this before every analysis and often discover surprising things! It is best to discover these things early, since they are likely to impact the final analysis.

If do you identify issues, check your data and correct as necessary. Once a data set passes these checks, we can move to next step: model fitting.

4.3 Step 3: Fit the Model

4.3.1 Notes on formula syntax and expectations

In this guide, we use lme4 and nlme packages to fit linear mixed models. These are similar packages that follow a similar framework and syntax. The general framework for lmer() and lme() models is to specify the response variable, fixed factors, and random factors and follow the R generic function for formula(). For this demonstration, let’s assume the dependent variable is yield, trt is a fixed effect and block is a random effect.

The code below shows the R syntax for a mixed model with one fixed and one random effect:

model_lmer <- lmer(yield ~ trt + (1|block),

data = dataset,

na.action = na.exclude)model_lme <- lme(yield ~ trt ,

random = ~ 1|block,

data = data1,

na.action = na.exclude)The parentheses are used to indicate a random effect, and this particular notation (1|block) indicates that a ‘random intercept’ model is being fit 3. This is the most common approach. It means there is one fit for each block. Here, note that random effects are specified differently in the lmer() and nlme() models.

3 Please refer to Chapter 3

na.action = na.exclude

You may have noticed the final argument for na.action in the model statement.

The argument na.action = na.exclude provides instructions for how to handle missing data. The option na.exclude removes the missing data points before proceeding with the analysis. When any observation-level model outputs is generated (e.g. predictions, residuals), they are padded in the appropriate place to account for missing data. This is handy because it makes it easier to add those results to the original data set if so desired.

We use the argument na.action = na.exclude as instruction for how to handle missing data: conduct the analysis, adjusting as needed for the missing data, and when prediction or residuals are output, padding them in the appropriate places for missing data so they can be easily merged into the main data set if need be.

Even when there are no missing data and this step is not necessary, it is a good habit to be in.

4.4 Step 4: Check model assumptions

Linear mixed models rely on linearity, independence, normality, homoscedasticity of residuals. Violating these assumptions can lead to biased estimates, inefficient inference, and convergence issues. Always check model assumptions, and if they are unmet, consider alternative model specifications.

In these model, the error terms, \(\epsilon\) are assumed to be “iid”, that is, independently and identically distributed. This means they are expected to be normally distributed with a mean of 0 standard deviation of \(\sigma\), or more specifically, \(\sigma \mathbf{I}\), which refers to constant variance and a covariance of zero between residuals.

In this guide, we well be testing these assumptions by using graphical methods. This can be done in two ways:

4.4.1 Original method

We can use base plot() function in R for lme4 and nlme objects to check the homoscedasticity (residuals vs. fitted values plot) of residuals.

plot(model_lmer, resid(., scaled=TRUE) ~ fitted(.),

xlab = "fitted values", ylab = "studentized residuals")plot(model_lme, resid(., scaled=TRUE) ~ fitted(.),

xlab = "fitted values", ylab = "studentized residuals")In this output, we expect to see a plot with random and uniform distribution of points. If we notice any specific pattern in the distribution of points, we need to look into the model structure and response variable distribution closely.

To check the normality of the residuals, we need to extract the residuals first using the resid() function and then generating a qq-plot:

qqnorm(resid(model_lmer), main = NULL); qqline(resid(model_lmer))qqnorm(resid(model_lme), main = NULL); qqline(resid(model_lme))The interpretation of the qq-plots generated from this code chunk is: if residuals falls closely along the 45-degree qq-line, it suggests normality of the residuals. However, if there is strong deviation of residual points from the qq-line, consider a different model that fits the data better. How to do this is way beyond the scope of this guide.

4.4.2 New Method

Nowadays, we can take advantage of the performance package package, which provides a comprehensive suite of diagnostic plots.

The diagnostic plots we created above can be created using one function check_model() from the performance package.

Read the documentation for check_model() to find what other checks this function can do. If you would like to check all assumptions you can use the argument check = "all".

check_model(model_lmer, check = c('normality', 'linearity'))check_model(model_lme, check = c('normality', 'linearity'))4.5 Step 5: Conduct inference

After verifying the assumptions of model, we can move to the inference of model. Based on analysis goals, we can either conduct analysis of variance using anova() function or we can estimate marginal means using emmeans() function from the emmeans package. We can also run a post-hoc comparison to evaluate the pairwise comparison or contrasts using estimated means.

Please remember that conclusions should not be drawn from models that don’t meet linear mixed model assumptions.